MEMOIR

…and Mistakes Made Along the Way, an excerpt from a memoir

by Fred Beauford

Chapter five: Mother

Hanging out in the projects and being a member of a street gang wasn’t all about listening to exciting music and dancing. It could sometimes be downright dangerous, and deadly. Also, I discovered that although typical New York teenagers in 1955 suffered from an existential dilemma that even Sartre couldn’t solve, blacks kids were filled with an additional rage that could surface at any moment.

I didn’t understand then, but do now, that this black rage was due to more than the typical teenage angst that inflicted almost every teenager in New York City, except, perhaps, Jewish-Americans. From what I could see, they went to school, had special classes after school in their religion and history, and never hung out with the Italians and the Irish, and certainly not with the few blacks. They seemed totally focused, and unaffected by all the angst swirling around them.

***Jewish kids notwithstanding, one evening in 1955, I was to find out first hand just how deadly this urban teenage discomfort could be

.As I have all ready mentioned, these street gangs could have branches in multiple Boroughs, plus shifting alliance. And, interestingly enough, given how segregated present day New York is, they weren’t necessarily all of one race, or one ethnic group.

I still remember that the guy with the biggest reputation in the mighty Brooklyn Chaplains was the only white member of that gang. I also knew two light skinned brothers who lived near me, who were members of the Italian Berettas. I remember them wearing the same black motorcycle jacket and jeans, their hair pulled back tightly in a modified “duckass,” just like their Italian buddies.

Our branch of the Edenwald Enchanters was all black, with the exception of two Puerto Ricans and one white guy. One of the Puerto Ricans was a short, mean tempered guy from the South Bronx. We called him Superman.

One day Superman had proposed at a meeting that we form a "brother club" with his old gang from the South Bronx, The Navahos. We all agreed. The first day our new friends, The Navahos, came to visit their new brothers they were wearing their colors, which were black and gold.

Unfortunately for them, the Edenwald Project was blocks away from the subway stop at 225th Street and White Plains Road, so they had to walk through the territory patrolled by the infamous Golden Guineas, most of whom were old friends of mine.

It turned out that my old friends, the Golden Guineas, had exactly the same colors and designs on their club jackets as the Navahos. They soon spotted the Navahos heading to meet us at the projects and chased their Puerto Rican asses back to the train station, sending them back to the South Bronx, lucky to be alive.

When Superman heard what had happened to his old buddies and our new brothers, he was furious.

He demanded a meeting of the Enchanters, which was granted. He demanded that we immediately declare war on the Golden Guineas. A member of the Navahos was in attendance at that meeting and told us that his gang had already declared war. That meant that by our agreement as a brother club, we really had little choice. We had to go to war.

The night of the "rumble," we were all to meet at the corner of 225th Street and Laconia Avenue, right across from the projects. As I stood waiting for the others to gather, I noticed that although a great number of Navahos had showed up, very few Enchanters were there, perhaps only four of us. I knew many members did not like Superman because he was Puerto Rican, and many thought he had a short man's complex because he was always "selling wolf tickets,” which was one day going to get him, or someone else, killed.

Also, I knew that nobody wanted to mess with the Italians, including me, and not only because some were still my friends. First, they surrounded the projects, and outnumbered us 10 to 1. Second, they were what can only be called more technologically advanced than us.

We fought with fists, sticks, garrison belts, switchblades and makeshift “zipguns,” which could explode in your face, causing more harm to the shooter then to any intended victim. We also walked or rode the subways and buses.

They had real guns, and drove cars. We knew that, and wanted no part of them if we could avoid it. As far as Richard and the rest of the Enchanters were concerned, these short little dumb ass Puerto Ricans from the South Bronx had come up here and started more trouble than we needed.

So, it was only me, Billy Barnes, Slim and Superman from the Enchanters, that showed up that evening.

We soon set out looking to encounter some Golden Guineas. We walked for a few blocks headed toward the Eastchester Projects. We soon encountered two white boys riding bikes. One was very tall and looked older than the other kid, although I found out later that they were both 15 years old.

We quickly surrounded them. Superman suddenly pulled out a gun. I was surprised and a sudden feeling of dread overcame me. I had no idea anyone was carrying anything other than a few knives. I also knew Superman's reputation.

I must say, that tall white kid had a lot of nerve. Here he was, surrounded by a bunch of blacks and Puerto Ricans, with a gun pointed at him and he was staring Superman down.

"Either shoot me or get that fucking gun out of my face,” I heard him say.

Badass Superman just stood there, staring back at the tall guy. The tall kid's friend did not look as brave, in fact, he looked scared to death. Suddenly Tarzan, or Frank Santana, as I now know him, grabbed the gun from Superman and fired one shot. I did not see Blankenship hit the ground. I did see a surprised, puzzled look on his face. We all ran. I went directly to my house near where the shooting took place and went straight to bed.

The rest of the Enchanters and Navahos, for reasons which defy logic, or common sense, went back to the corner of 225th Street and Laconia Avenue and stood around, colors blazing.

The police had an easy time rounding them up. Everyone who was there at that killing did time, with the exception of me, and tall, bony Slim, who also managed to avoid arrest. No one told the police that I had been present, or my life would have taken a far different path than it did.

This killing caused a sensation and was one of the shocking crimes of the 50s. Tarzan faced the chair, but his lawyer Mark Lane got him off with 25 years to life. He served the entire 25 years.

***I was on my way to teaching my media history class, as an Associate Professor at SUNY, Old Westbury, on February 17, 1993, when I opened a copy of the Daily News and my personal history stared out of the pages. There was a large photo of a young seventeen-year-old Frank Santana, in a leather jacket and looking glumly at a semi-automatic, which he had just recently used to kill someone. It was accompanied by a full-page story by Juan Gonzalez, detailing the sensational William Blankenship murder in 1955.

I was standing right next to the young Santana, who I only knew then as Tarzan, when he pulled the trigger.

I also learned that it was the shooting of Blankenship, along with other conflicts between Puerto Ricans and Italian street gangs, that inspired Leonard Bernstein to write West Side Story, turning the shooting into a modern version of the Romeo and Juliet story, while leaving out the blacks.

For the young Santana, however, there was no lovely Maria singing to him from the fire escape; just 25 years of hard time in the state pen.

Mr. Bernstein and many others made millions telling Superman’s history, Tarzan's history and my history. But was it history?

***In only a few years, the conversation among the gang members started changing, as one by one, they began their introduction into the criminal justice system. Names like “Warwick,” “Elmira” and “Rikers” became a part of our everyday conversation. Warwick was the upstate reform school for kids younger than sixteen. Elmira was an adult jail located in upstate New York, where the older ones went. And Rikers Island was the local New York City jail. As the arrests grew, I would listen to long conversations about who was the meanest judge to face. Everyone agreed that it was the much feared, “Lebowitz.” This judge showed no mercy to the young black men who stood before him, and everyone knew that if they were unfortunate to draw him, it was goodbye for a long, long time.

It was many years later that I discovered that the infamous Lebowitz, whom everybody feared, was none other than Samuel Lebowitz, the lawyer who defended the Scottsboro Boys, in one of the most famous trials in American history. This younger Lebowitz, in 1931, volunteered to go to Alabama and take up the cause of the nine black teenagers accused of raping two young white girls in a boxcar which all of them had stored away on. This was at a time when the Northern European settlers in the south hated Jews as much as they hated blacks, and didn’t mind murdering them, either.

Up until this time, Lebowitz had been known only for defending mobsters, but he worked diligently on behalf of the Scottsboro boys, taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court, unintimidated by the great dangers he faced.

But now, years later, looking down on my friends from the Projects, this new Lebowitz, who had become world famous by helping save a destitute group of young blacks, and was made a judge in New York City for his heroic effort, had little mercy left in his heart for anyone young and black.

***Perhaps you have noticed by now that I have not included myself among those who had to face the wrath of a Lebowitz. To this day, I have never spent one day in jail. In fact, the only time I have ever been arrested was for an outstanding warrant for a jaywalking ticket, I received in Los Angeles . I spent a few hours in jail until a friend bailed me out.

How did I do it when everyone around me, including Richard, was getting arrested on a regular basis?

For one, my mother sent both Robert and I to stay with our Grandmother on the large farm buried deep in rural Northern Virginia the very next day school was out, and we did not return to New York until the day before school started again. This happened until I was sixteen. As to be expected, most of the mayhem in the Projects, including young girls getting knocked up, at least four or five kids getting arrested, and someone either getting killed, or almost getting killed, or killing someone -- occurred during the summer months, and I missed out on all the action. Why she didn’t send Richard along with us I will never know, because as a result of his staying in the city during the summer, his rap sheet just grew and grew.

But there was something else that kept me out of jail. I have two major traits that have served me well over the years. For some reason, I have always had an unerring sense of when it was time to leave a situation. I would suddenly feel in my inner marrow that things were going to become progressively worse. Perhaps it is because of my life-long ability to step back and evaluate, as a good novelist does, almost as a “fly on the wall,” as a friend in San Francisco once dismissively said of me, and react rationally to a difficult situation, not emotionally.

Again, this is a trait that has often, until this very day, caused blacks, Hispanics, Asians, as well as whites – to look accusingly at me with narrow, unforgiving eyes, for being a bogus black, someone with ice water for blood, and someone not to be completely trusted.

An example of this trait in full flower was the first time my friend James Johnson was sent to jail. He and some other kids had stolen a car. I remember the car just like it was yesterday. It was a bright yellow and black Mercury. They had parked the car on Laconia Avenue that night and everyone went home. James told me about the car when I arrived at his apartment the next day. We soon joined four others at the car and were planning on going on a joyride. Everyone piled in.

For reasons unknown, something in me said, ”Don’t get in that car.” I begged off.

“Aw, you jive-ass motherfucker, always got to do something different,” one of my friends, who obviously didn’t care that much for me, yelled.

That is my other lifelong trait: I am unmoved by peer pressure. My good friend Herb Boyd, the great writer, just said to me just recently, “You don’t seem to give a shit about what people think of you.”

Boyd is right, and on this day this trait paid off. I dismissed the harsh comment, unmoved, even coming from one of my friends, and watched as they pulled away. As soon as they drove from the curb, another car pulled out right after them. I knew instantly that that was not a good sign. The next day I went over to James’ apartment. His younger brother, the tall, gawky Willinsey, answered the door.

“Where’s James?” I asked.

“He’s in jail,” he replied.

“No shit!”

It seems that the stolen car had been staked out, just waiting for us to come back to drive it. The car that I saw pull out after them was, of course, the police, and stopped them only a block away. Everyone went to jail.

Soon, this uncanny luck I had of staying one jump ahead of the law, was beginning to generate much teasing. “They are going to get your black ass sooner or later,” became a constant refrain. I was reminded of this in a scene from the movie Goodfellas, when all the wise guys came running when Henry Hill was finally arrested for the first time.

“I see you lost your cherry,” one of the mobsters gleefully yelled to him, as the police led him off to jail.

But I never lost my cherry, so to speak.

One night, soon after that incident with the car, I thought my luck had finally run out and my black ass had indeed, been finally beaten.

About twenty of us had been drinking our favorite drink, white port and lemon juice, under the “wine street.” That was a large tree we hung out under, in a patch of woods in the front of the projects. Uptown Bronx at that time was still very underdeveloped, and patches of woods and empty lots abounded.

If I remember it correctly, what set us off was that someone started talking about what had just happened to Emmitt Till a year earlier in Mississippi. The Klansmen who had killed him had just been acquitted in a recent trial. The more we drank, the more we wanted to go out and bash some white boys’ heads.

After getting as lit up as one quart of wine could do among so many eager mouths, we soon headed out toward the Eastchester project; interestingly enough, following the same route I had followed a year ago, which had led to the murder of a 15 year-old white boy. We arrived at the middle-income project without incident.

We quickly encountered several black kids sitting on a bench. My brother Richard promptly got into a fright with one of them and knocked the guy out with one punch.

We left the project pumped up, with the guys excitedly chattering away, saying among other things, “Man, did you see that shit! Can you believe it? .Man, did you see what Rabbit did? Bam, one punch and the nigger was out cold.”

As I have said over and over in this memoir, my older brother was very capable of doing wild and crazy things.

And just like that night with the Puerto Ricans from the South Bronx, we soon ran into two young white boys riding bikes right outside of the Eastchester projects. We surrounded them, and Benwine, one of the seniors, who got his nickname because he drank copious amounts of white port and lemon juice -- and anything else with alcohol in it -- suddenly pulled out a knife.

For reasons unbeknownst to me, I said, “Leave them alone. They’re just little kids.”

It just didn’t seem right to me that 20 of us were picking on two, scared kids. At least Richard had squared off with someone his own size and knocked his dumb black ass out with just one punch.

What was so brave about what Benwine was about to do?

Benwine gave me a dirty look, and said to Richard. “How come that little nigger of yours always got something to say?”

“Aw, come on, forget about it. Let them go,” Richard said. Before we walked away, Benwine reached over and smacked one of the white kids hard upside his head.

“That’s for Emmitt Till,” he said.

I was furious. I thought Benwine was a fucking coward. What the fuck did he prove by what he had done, hitting that kid like that! I was deeply ashamed for all of us. On the way back to the projects, I was walking alone in the back of the group, disgraced and sulking. Up front, conditions became increasingly rowdier as someone -- I think hard-hitting, mean Lennie -- threw a garbage can through a basement apartment window.

“That’s for Emmitt Till, motherfucker!” he yelled.

The guys ahead of me were breaking off car antennas, smashing windows, and thank god no white person was encountered on the street, or else they would have been dead meat. As we neared Edenwald, all at once I saw at least a dozen police cars come out of nowhere and surround the guys.

Because I was way in the back, alone in a deep funk, I was not caught in the trap. I dropped down exactly where I was, and hid in the grass and bushes. I was soon able to make my way home, undetected.

To my surprise, when I arrived home, Richard was already in bed, sound asleep. They didn’t call him Rabbit for nothing.

In a few minutes, I was asleep, as well. But my peaceful sleep was soon interrupted as my mother came into the room and woke me.

“The police are here. They want to talk to you.”

“Me? Why?”

“Just get dressed and come out and talk with them.”

As I left the room, I heard Richard snicker. “They finally got your ass,” he said, laughing.

The two policemen were ready to lead me out the door and down to the station house when I asked, “What did I do?”

One looked more closely at me. “Wait a minute, do you have an older brother?”

“Yeah.”

“What’s his name?”

“Richard.”

“That’s the one we want.”

I went back into the bedroom. “They want you, not me.” I climbed back in bed, and was soon fast asleep as Richard was led away to jail, and spent the next six months on Rikers, where he joined James Johnson and the other four guys from the stolen Mercury. It was Old Home’s Week at Rikers, as all of the older boys served at least four months, with Richard serving the longest time for that night of wine driven, politically charged mayhem.

Once again, I had escaped having to face an unforgiving Lebowitz, and once again, no one gave me up.

The one code we in the Edenwald Enchanters strictly adhered to, above all else, was that no one ratted on anyone; although someone -- a quiet, unknown enemy perhaps, who harbored great resentment at Richard’s dominating, outsized personality, and the fact that all the young girls in the projects were crazy about him -- had clearly ratted on him, because the cops knew who they wanted, and where he lived.

But, as I now think about it, maybe that wasn’t the case at all. Maybe it was just a watchful God giving me a thumbs up, and a reward to return to my quiet, peaceful, warm bed, unmolested, for having the courage to speak up, and save those two young white boys from Benwine’s knife.

And if I hadn’t spoke up, this God undoubtedly knew, being so wise, and able to peer far into the future, that Richard and Benwine, and perhaps myself, would probably have faced the same 25 to life that the young Santana faced.

***At this point, I should say a bit more about my long suffering mother, as she tried to manage four children -- our half sister had recently joined us -- in gang-ridden New York City in the 50’s, with at least two of us slightly crazed, testosterone charged knuckleheads, all by herself. My mother died in April, 2006, at the age of 87, as I was in the middle of writing this memoir. Her mother, my beloved grandmother, lived to be 92. (I hope that genetic gift of longevity has been passed on to me!)

As I have said, my mother didn’t have that much to say to us, and was especially tightlipped about the job she faithfully went to, five days a week, and often on weekends, no matter what the weather was like outdoors.

There were obviously many questions in the back of my mind about her. Where did she live, and what did she do all those years we were apart? Why did she suddenly come and get us? Why did she then move us to an almost all white community?

How did she even find this place, so isolated, so underdeveloped, at the edge of the northwestern Bronx in the first place? Why did she always act so passive at all the shenanigans performed by Richard and me? I can never remember her yelling, or threatening us when we got into trouble, in all the years we lived together.

There was something far different about her than the mothers I met from the Edenwald Houses, or even the Italian mothers I knew. I had never seen even a vague hint of violence coming from her. I saw something vaguer, however, something which later, slowly, but ultimately, revealed itself fully to me.

I came to realize that my mother was a snob; that she really saw herself as an American aristocrat.

Many years later, thank God long before she died, and we became real friends, that I finally understood her.

The Jewish and Italian folks she encountered, no matter how much money they had, or the color of their skin, were in the end, still just immigrants, settlers, aliens, chased out of Europe by who knows what.

She wasn’t afraid of them. And it wasn’t her simply putting on false airs. I learned that her pride was something that she felt deeply, and that this was her self-image. Over the years, in my 50s, I discovered that as uneducated as she was, she still had a deep, intuitive understanding of the history of this country, and of the south, and her place in it; she fully understood the African and English blood (DNA) she carried, and it didn’t conflict her.

Perhaps the most important thing she carried around with her, which she spoke of quite often -- adding that she alone was saving the place because she was the only one paying the taxes on the land-- was the fact that her father was once the largest black landowner in Northern Virginia, and that her grandfather was an Englishman, who had owned the property before my Grandfather acquired it, and all of that land is still in our family’s hands, to this very day.

(An aside … millions of acres of land were lost by African Americans in the South during this period, simple by them not paying the taxes on the property, sometimes only as little as $120,00 a year, which was what my mother faithfully sent the County each year.)

***She obviously idolized her father, and I can see why few of the black men she had encountered in the north, and continued to encounter, given how attractive she remained until late in life -- never quite measured up to her standards.

This includes my father.

She reminded me every chance she got, that Grandfather was a “genius,” and not so subtlety imply that she had inherited his great gift. She didn’t have to convince me, however, that he was an extraordinary being. As you readers know, I had seen it first hand.

***I am convinced that that was what gave my mother such a quiet, supreme, self-confidence.

(Another aside. I can hear a collective gasp and sudden recognition from those blacks and whites reading this, who know me well.:

“OMG. No wonder he’s so damn weird. He takes after his mother, for God’s sake!”

“He really thinks that he is a latter day American version of Louie the 14th, just because he has a French last name.”

***Not quite. But close.

***I never once heard my mother complain about being an African American. To her, in many ways, it was a badge of honor. I realized later, that she felt at the very bottom of her being, that was made her a “real” American.

This was in startling contrast to Mrs. Thompson at The Home in Buffalo, as readers of this memoir well know.

***I could not imagine my mother hitting me, no matter what craziness possessed me. Maybe she knew by the way I often snuck quick, hot teenage glances at her, that I saw her as an exceptionally attractive woman. I guess she knew that I had fallen in love with her, and that I couldn’t quite believe that such a lovely person was really my mother.

***She would only sigh in resignation at Richard’s, or my, latest adventures. Robert, on the other hand, was a quiet, steadying force, and not prone to high drama.

Perhaps she was just overwhelmed by all of this sudden responsibility, and didn’t know what to do, or say.

One of my best friends from the Projects, Buzzy, the guy with the beautiful, light green eyes and handsome, baby face, was committed to Warwick at the age of fourteen for doing half of what I was able to get away with. I can only now imagine what someone so good looking as Buzzy faced in jail at such a tender age, even though it was only a reform school.

When he told me that his mother was sending him away, I couldn’t believe my ears. My mother would never think of doing something like that to Richard or me, although we probably deserved it more than Buzzy.

She just sighed, and sighed.

******Slowly, I was able to piece together the fact that she worked for several wealthy Jewish families, as the help, as it were. One was the Chairman of 20th Century Fox. She had worked for them for years as a maid, cook and nanny. One family lived on Sutton Place in Manhattan; the other, the Freyberg’s, lived in Westchester County.

The only real insight I got into her world was when she once told me, with a dreamy look on her face, that the apartment on Sutton Place was “the closest you could get to heaven without dying.”

But it was the Freyberg’s that always held my interest. One day my mother seemed very upset over something. She let it slip that one of the Freyberg’s had just committed suicide. “I just don’t understand why she did that, that poor woman,” she said to me, in deep sadness. She obviously harbored strong feelings for that person because that woman’s death obviously haunted her, and she kept coming back to it year after year.

She kept a small photo of the three Freyberg’s children next to her bed. She had helped raise them from infancy. Although I didn’t know them, and never met them, I hated them with a passion. I was jealous, plain and simple.

This was my lovely mother, no matter what they thought!

***There were several lessons I learned from my mother as a teenager, when I wasn’t out in the street acting like a fool. The first was that I learned to cook, and when you do cook, always have something green as part of a balanced meal to go along with the steaks, chops, rice, or potatoes. And don’t drink stuff like Kool-Aid, but rather orange juice, water or some other fruit beverage. This was a far cry from the grim Dickinson plate of pinto beans, or plate of rice, or plate of potatoes that Mrs. Thompson placed before us nightly

My mother was the most organized person I have yet to meet. I would watch closely as my mother quickly whipped up the tasty, well-balanced meals she served us every night, all the time complaining about how hard she spent her life working for us.

This constant complaining would make me feel guilty, as if her personal misery was my fault. I developed this trait of feeling personally guilty for other peoples’ suffering, as if I was some kind of failed God who hadn’t delivered on my promise of universal happiness for all.

I wanted to say to my mother, “Let me cook. See, I know how.”

I once gathered up the courage to ask her to let me fix dinner, but it was not to be. She quickly shooed me out of the kitchen, not giving me a chance to show off the tremendous cooking skills I knew now existed in my mind.

I understood what all that complaining was about, however. In essence, she was asking me for some kind of forgiveness for the years of neglect and mistreatment that Richard, Robert, and I had suffered at the hands of Mrs. Thompson.

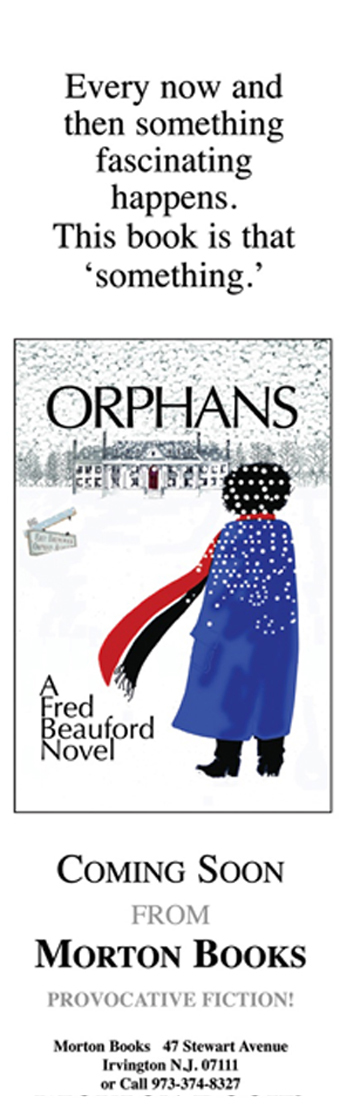

Perhaps because of spending key developmental years in The Home, which I explored fully in my novel, Orphans, I now know I am unable to read people fully, and I am prone to believe that people are what they say, and not what they do, even at this late age, when I should know better.

I was greatly distressed that my mother worked hard all day and then had to come home to cook for us; because that’s what she said, despite the great, loving care I saw her take with each and every meal.

One consequence of my wanting to learn to cook so that I could relieve the heavy burden placed on my mother was that I did turn out to be a good cook, just like her, and just by watching her at work.

I have been the cook for all of the women I have lived with over the years (my last girlfriend even had the nerve to accuse me of making her fat!).

My two youngest kids grew up in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City, with apartments and houses filled with wonderful, tantalizing aromas. And their friends would flock to our place, especially when they were greedy, ever hungry teenagers, because they all knew they could expect a good, home cooked meal, not a television dinner, or worse, MacDonald’s.

(The last aside. As an adult, I still get very annoyed and non-understanding of people who can’t cook. All it really takes is a little bit of this, a little bit of that, and overseeing, and watching over the preparation carefully, as you would a growing baby, until it all comes together. It’s certainly not rocket science, and is one of the easiest things in the world to master; not to mention all the money you save and ill health you can avoid, by being able to quickly toss together a tasty, well-balanced meal!)

The other lesson my mother taught me was the concept of moderation. She firmly believed that you could do almost anything under the sun, if only you could learn to do it in moderation. Our meals were served in small portions, with room left over for dessert. She drank alcohol almost every night until her death, but I never once saw her drunk. To me, moderation, while often very difficult to live by, was a lesson to cherish.

Except for gout (perhaps because of too many, rich, well-cooked meals) I have so far escaped ill health and obesity, despite my drinking, smoking, and sometimes acting the fool with loose women. I am convinced that part of the reason is my ability to feed myself well, no matter what my income level, and to do whatever evil to my body I am prone to, in moderation.

Mother was right.