SHORT STORY

You Must Remember This

by Jan Alexander

From Tara Mason’s Money Memoir. We bought a house. Nick said real estate was always going to appreciate. My husband with a brand new PhD in economics; he used the word “appreciate” that way. It was a farmhouse near Woodstock, with a robin’s-egg blue front porch and plenty of room for the kids we were going to have someday, including a detached garage with an upstairs apartment. We worked in New York but we could flee the city on weekends. We paid $10,000 more than the asking price to win the bidding war, but Nick said we’d get that back in equity in no time.

Owning equity—a dustball of equity, really, but that was okay too—made Nick start looking at the world the way a grownup does. I helped him pick out classic horn- rimmed glasses that proclaimed here is a man too mature and cerebral to follow what’s trendy. He turned his dissertation into a book. My mom and dad watched him on television.

“Don’t you ever let him slack off, baby,” Mom said on the phone. “He said smart things but you know, he didn’t keep his eyes on the camera, like he didn’t really want to be there. Even a guy with a PhD can screw up. Can you send us his book? How much does it weigh? I wish I could buy it but you know…. ” I knew, and my husband didn’t, what it was like to have parents who can’t afford to buy his book.

Nick’s first book, as a TV talk show host was generous enough to say, was called The New Derivative Power. One reviewer praised it for the colloquial parts. Nick wrote about how he’d just bought his own first house and paid a lot but that was okay because real estate is forever. What made it a sure thing? That was the new paradigm. The United States wasn’t doing so well with making automobiles and widgets, he wrote, but on Wall Street some bright mind had figured out how to take a hundred mortgages and bundle them up into a bond that big investors could buy then sell, and that’s an example of a derivative instrument—it takes something else and derives its value. I watched him say the same thing on camera, true, looking like he knew he was saying the right things but still didn’t want to be there. He wrote, and talked in dozens of lectures and TV appearances, about how Wall Street had this innovation called derivatives that could make money grow with the same kind of inevitability that turns a sprout into a tree. We can now trade anything, he said. People will buy houses and they’ll grow in value. Someday someone on Wall Street might offer your kid money to put her lemonade stand into a derivative. (I made him inject the “her.”)

Then it turned out he was all wrong.

Banks collapsed. They’d spent more capital than they had speculating in derivatives made out of mortgages to people who couldn’t afford to keep up the payments. That was the way my economics professor husband explained it to me. I wish I didn’t need to know these things, the same way I’d prefer to not know that my favorite fashions come out of sweatshops. Capital, I figure, grows in a place that’s hotter than a coal mine, then makes its way through the bowels of some secret clubhouse where men with indistinguishable faces spend their days dreaming up stun-gun words—“capital gains,” “collateralized debt obligation”—meant to induce outsiders like me into a coma. My job was editing and writing articles about fitness and relationships and movie stars’ yoga routines or trips to Somalia to adopt an orphan, but even at my office everyone was talking about this rogue army of derivatives attacking us.

At the end of the fall semester the head of the Columbia economics department called Nick in to say they’d decided he wasn’t quite what they were looking for in a tenured professor. The decision didn’t even get past the department up to the university committee. They would have let him teach there another three semesters, but Nick said “Fuck you,” to the department head. He told me he said those exact words. And that he was packing up after the spring semester.

My mom made sighing noises on the phone. “A hot-head. Not good, honey. He’s prob’ly mad at himself ‘cause he got everything all wrong, don’t you think? But you gotta look out for yourself too.” I reminded her that she was still with Dad. But that was her point and we both knew it, that my dad wanted so much for me he was willing to get caught up in a crime to pay my tuition, and I wasn’t supposed to blow it all by marrying a hot-head.

None of my girlfriends from Brown would have had to think this way. Nor would any of my friends or not-friend-colleagues from the women’s magazine where I worked.. Well, maybe they would re-examine the situation because they’d all prefer rich husbands over poor ones, but they all had parents who could send them money if they needed it. Whereas I was sending my parents a few hundred dollars out of every paycheck, and sniffing around for ways to get into the editor-in-chief spot so that I could send them a lot more.

Money—no, not money, but lack of money—is like a filter over your eyes that tints the one you love. And I did love Nick, at least at the beginning.

When I met him, six years before the mess that people now just call The Financial Crisis, we were at a party. He stood out even though all the men looked more or less like him. Ivy League types with that symmetry to them, guys whose clothes got wrinkled only in the right spots, guys who could talk about sports scores or the economy or even taking out the garbage and make it all sound like something vital to the well-informed. What I noticed about Nick was his secretive half-smile, like he’d seen sad and scary things. I made sure that wherever he was I’d be across the room gazing at him. Bold stuff for a girl from a flat, prefab-home kind of place, but by then I’d learned a few things about transforming myself through the power of an attitude, elegant clothes, a yoga-and-swimming glow and an antenna to filter out social interactions that drifted in the direction of boring. Months later Nick said, “You were looking at me like you wanted to save me from my worst instincts.”

He grew up in places the indigenous population knew as “the doctor’s house.” He wasn’t rich, it turned out; his parents had come from money but given most of it away to various African villages. When I married him I knew I was cheating our future children out of his easy air of expectation; one scrappy generation is all it takes to be always looking out for scraps.

On the other hand, he made me feel like I’d never been anything else but Tara Mason, graduate of Brown, resident of Manhattan, editor at a chi-chi magazine. He was capable of pretending—I saw that when he met my parents and told them his own grandparents were retired in the Florida Keys, when actually they were retired in the south of France. He made my mom and dad feel like he wasn’t too grand for them after all, even if it took a socially-gracious lie. He made his friends and even his oh-so-self-righteous mother think I was not so far from being one of them, having climbed up to the Ivy League through the class valedictorian route. West Palm Beach would have been too unrefined for them and Palm Beach way too flashy, so he just told them I was from Miami and my father was a private detective: humble but with a touch of intrigue. And they were thrilled when I explained I was a little bit black, on my mom’s side, and not a Miami Cuban, which would have been way too right-wing for them. “Huh?” my mom said when I tried to explain it all to her. “Guess I should have moved to New York when I was young.”

When Nick didn’t get tenure he said he wasn’t cut out for academia anyway. He was going to write something. Or make a documentary. He taught his spring-term classes but otherwise he didn’t seem to be doing much. I’d come home and find him slouched on the sofa, watching videos. Sometimes other movies, but mostly Casablanca. That’s what he was watching the afternoon I came home early, with two heavy totebags on each shoulder. I’d swept the pens and stapler and 10-years worth of promotional gifts off my desk after the editor-in-chief called me in to say they had to cut back and that meant my job.

My husband, unshaven and wearing sweatpants, made two vodka martinis.

“Nick’s place instead of Rick’s place,” I said. “We’ve got our own war out there, you know.”

He looked at me as if I’d hurt his feelings. “I can still get a teaching job you know. It’s not like I single-handedly caused the crisis. Bard wants me to teach a class in the fall, did I tell you?”

He had, several times.

“People get by on a lot less than we have,” he said. “Here’s what we should do. Get out of the city for good. Rent out the house and we’ll go live upstate in the garage apartment.”

Bard was near our country house, so his threat was real, even sensible if I were to give up on the glamorous publishing world that had just cast me out.

I said, “Poverty isn’t an adventure,” but the words almost vaporized in a cloud of vodka. He gave me a look that said of course it is. He was sitting upright instead of slouching, like a pilot at the controls, like he was all ready to take off and discover some lost continent.

In the city we lived in a two-bedroom apartment not too far from Columbia, a good deal because it was an illegal sublet, though there was always the possibility the landlord would throw us out. The city apartment had a cerebral funkiness, with the peeling plaster and book-lined walls. The house upstate had mountain breezes blowing through the windows. I loved both. The garage apartment upstate had wall-to-wall carpet embedded with the smell of beer brawls from before our time there, and we were afraid worse things might lie below. It had only two windows, both overlooking the land beyond our acre; specifically, three flimsy houses that had supplanted farmland sometime in the last two decades. The people in those houses scraped their living from the home repairs and whims of the weekenders, not unlike the way my mother emptied bedpans for sick billionaires in Palm Beach and my father—before he got into trouble and lost his license—used to stake out their cheating spouses.

“I won’t live there,” I told Nick. We fought for a week. Then we came up with the Treaty of Three Residences.

A woman named Melissa answered our post on Craigslist and said she loved the house. She was 29, six years younger than I was, and already had two toddlers, a divorce in the works, and an awful story about how she and her ex had bought a nice house with no money down, then lost their jobs and found out the mortgage interest tripled after two years. Melissa claimed she pulled a shotgun when the sheriff’s deputy came to foreclose. She was working again, as a hostess at a restaurant on the road to Woodstock, and she paid a month’s rent in cash upfront.

Another woman, a graduate student, answered my post about sharing the apartment in the city. I would stay there during the week and look for freelance work, then take the bus upstate on weekends. May came, Nick gave his final exams—he gave A-minuses to everyone without even reading the bluebooks—and he moved up to the garage apartment. All week. All month. He wasn’t sure if the class at Bard would fly, but he was going to plant a garden and paint the porch on the house and figure out what to do with his life.

Compromise.

Have I mentioned that our car was dying? It was 15 years old. We couldn’t turn on the air conditioning, or the engine might stop. A rear fender dragged. In June it clattered, like old cans scraping asphalt; that was a tail pipe repair that cost $248. In August Nick picked me up at the bus station one Friday night, and I heard the car choke when he started it up.

“I have to start in second, first gear is fucked,” he said. “That’s going to be another $300. This slow bleeding… we’ll just have to get rid of the car, but it’ll be good for us to bicycle everywhere.” Even the timbre of his voice was ridiculous, like a classical pianist trying to pluck on a banjo. A wife with a job would have laughed at him. But I knew about cars with peeling rust on the outside, cars that wheezed down the highway, cars that stunk from the layers of grime on torn seats. My mother had such a car, and when it broke down she had to skip a day of work.

“Poverty isn’t an art form,” I said. That would rile him, but I knew no other tactic. Nick had changed since May. He seemed to spend his days adding and subtracting one- and two-digit numbers.

“Tell me I haven’t made an art of it. Waiting for you in our humble little garage apartment is a feast of poached salmon. On sale at Price Chopper for two dollars a pound. And yellow cherry tomatoes from the garden, and the best under ten-dollar Riesling….or did you spend your money on a deli sandwich?”

I wasn’t hungry.

“You’d better start saving because we need to replace stairs. We’ve got two rotting, the third one up and the top one. And Melissa says she’s got a leaky faucet so we’ve got to get a plumber, and the house needs new gutters. Before winter.”

“Seen the baby raccoons lately?” I still came up to see nature.

The car had carried us home by then, in third and fourth gear. The tree-frogs were crooning. The moon was a sequined sliver. Country bling against a fresh-scrubbed sky, but it seemed like even the cosmos wasn’t as flashy as it used to be. I took off my sandals and let my toes squish through the grass.

“You’re going to get ticks,” he called out.

The grass belonged to a zillion little creatures, not to us. Nick was talking about the $50 co-pay our cheap insurance would charge if I were to get Lyme disease symptoms. “And they probably won’t even pay for the medicine…c’mon, you can’t afford this.”

He still knew the right things to say when he wanted to, though. He gave up on the tick ploy and said “come and let’s play in bed.”

He was on the top step. From my gaze below, the symmetry was still there. He’d found a bargain hairstylist in this little town, a bargain ten-speed to keep fit. Women up here must notice him, strolling alone through the produce market or the hardware store. Four nights a week I was rehashing the scenarios with my friends in the city, that he might start having an affair and who knew, he might come back to life out of his desire to woo someone else, but wouldn’t that be better than a permanent breakdown? Then I’d sigh—don’t sigh, you’re never going to get a new job if you sigh in interviews, one of my friends had admonished me just that week.

I heard myself sigh before I mounted the stairs. We stood on the landing together. From there we could see our house. Melissa’s grill on the patio. Roses growing up a trellis. From inside, lights flickered and muffled voices upstaged the crickets and tree-frogs. Melissa kept her television on all the time. Nick always said she must hate the sound of her own thoughts.

“…go back to Bulgaria…” That smoky tough-guy-hero voice bounded through an open window. Like the ghost of Nick living there.

“Holy shit, she’s playing it. She came by last night to tell me she knew she was late with the rent, I was watching Casablanca and I said she could borrow the old tape. That car over there—see, she’s got a date. Maybe you weren’t paying attention but there’s another car on the road just sitting… an old Chevy with a bumper sticker that says, ‘It’s okay, I’m with the band.’ Didn’t she say her ex was a musician?”

“If her ex is sitting out there in wait we should call the cops.” I was almost proud of myself for thinking of our tenant’s welfare first, before my husband’s obsession with Casablanca and the fact that Melissa had paid her July rent on July 24, when we’d made it clear it was due on the first, and was now a week late with August.

“If she’s being stalked she’s gotta be the one to report it.”

“What if he shoots bullet holes in our house?” True, I was thinking of that too.

But Nick was opening the door and nattering on about the salmon. He talked pretty much all through a dinner that I savored in small bites. He talked about the neighbors down the road and a college friend who’d visited during the week and the price of coleus because some ground cover would be pretty, and the handyman who could fix the steps as soon as we could afford it. He talked about the number of students who’d enrolled early in his fall class at Bard: three. Three more and the class would be on. Then he beckoned me to the bedroom. Later he fell asleep on top of me. I rolled him over. A flicker of moonlight showed the groove in his forehead that was turning into worry lines. My diaphragm felt like leaden weight and I couldn’t sleep. In the city the ponderousness of being alone kept me awake. I was grinding my teeth down. I’d written one article for money and two blog posts for nothing except exposure about all these stress hazards.

The apartment wasn’t quiet. Paratroopers were landing on the roof; pinecones, really, or maybe squirrels. I got up and went into the living room.

Nick knew how to strew a food-stamps kind of apartment with enough inherited furniture to make it look like the kind of home where art and books and noble deeds might comfortably reside. He washed dishes, he kept salad in a spinner in the fridge and peaches and berries in the bin below, no junk food except the foot-long salami down a few inches from last weekend. I smelled marijuana in the chair fibers and found the roachclip beside his computer. The computer was on. I had a right to know if he was doing anything productive, didn’t I? I looked for new files and found nothing. I knew his e-mail password but never went that far. If he were having an affair would it be a woman who didn’t push him? Or maybe one with a Wall Street job and an estate up here?

An 8 x 10 notepad had some new scribbles. My heart thumped, hoping to find a big idea.

The notes said, “5 gallons high gloss. $40/gal,” and the name of the local hardware store. “Lowe’s primer $33 gal.”

He’d built a wall of shelves for his books and arranged everything by category, each category alphabetized according to the author’s name. The New Derivative Power was there too, in the economics section, stuck out an inch from the other books, an assassin stepping out of the shadows.

“Yoooowwww!” A falsetto shriek from outside. “Yooooowwwww.” More desperate the second time, like a mad wolf dying alone.

“Darling….” Nick had come into the room. He was hoarse and sleepy, but he’d put on his summer robe. Just in case a servant happened by no doubt. “Those damn fisher cats—you must have heard that yowl. I woke up and I thought aren’t you supposed to be here? That’s, uh… I heard them the other night. They’ll tear your limbs off if you run into them. They’re called fisher cats but they’re not a cat, more like a what is it, a skunk… no a weasel… or …”

He sat down beside me, stretched his arm across the sofa. I moved close and thought of going to his computer to look up fisher cats. Could I trust any information that came from him?

He turned on the DVD player to the place where Humphrey Bogart as Rick was saying “If she can take it so can I.”

Nick said, “Mum e-mailed and asked if we want to come for Thanksgiving. She didn’t offer to pay though.”

“’Course… you should tell her.”

Nick’s mother was in Nairobi now, too busy treating people with malnutrition and AIDS to have even read her son’s book, she’d admitted, and well, too bad about not getting tenure but your father kept going even with cancer, I’m sure you’ll end up at Harvard after the next book honey.

“Maybe you can interview her for another story.”

“Been done. It’s not like it’s a movie star crowned by HIV orphans photo-op kind of thing. Anyway….”

Anyway it was a moot point. I would have loved to edify my West Palm Beach brain with another trip to Africa, even though it would have required tolerating Nick’s mother with her habit of looking me up and down and saying nice blouse, nice shoes, you’re the most fashionable thing we’ve ever seen in the outback, all with an undertone that said you frivolous arriviste you.

“We can’t drive down to your family, the car won’t make it,” he said. “Why don’t we just stay here and tear up the carpet? It’s December 1941, what time is it in America? Funny about whatsername.”

“What’s her name?”

“You know. Melissa. If she has a date she said here, my landlord leant me Casablanca….”

“All men love it. When my dad bought his first VCR player, it was the first video he bought.”

“Girls who love their fathers call them ‘my dad.’ You sound so fucking wholesome.”

For a moment I almost believed I was fucking wholesome. Nick is very good at telling people what they want to hear: that was the conscious thought that hit me. I tried to remember when the effects of his charm had started to become temporary and traced it back to derivatives. I thought of a particular night, even. He’d been working on the book, he’d told me something about the power of derivatives and I’d suddenly felt nauseous. I’d sat in the bathroom, thought this must be it, I must be pregnant, I put my hand on my stomach and even imagined something was kicking—but I wasn’t pregnant and what I remembered from that night was sitting on the side of the bathtub taking deep breaths and trying to pushing away a question: Does Nick worship derivatives just because this is how he’s going to make his career?

Now, sitting on the sofa with him I said, “It’s the hero with the gruff façade thing. It’s all so clear-cut, Humphrey Bogart can be anyone because it’s what he does that counts, not what he says. Claude Rains shuts down the café and he says he’s going to pay everyone their salaries anyway…. And it’s a guy’s kind of romance since he lives with ‘we’ll always have Paris,’ not in a farmhouse in upstate New York with a nagging Ingrid Bergman.” The perfect fantasy world for a guy who isn’t near measuring up to his parents’ definition of a hero; I’d thought of that months ago but as usual, ground my jaws together and willed my mouth to stay shut.

“Shhhh…I wanta see this part…”

We didn’t go back to bed until Claude Rains and Bogey turned their backs on the screen. We lay intertwined. Nick mumbled something about “Would you find out if it’s too late to plant pumpkins and squash… you know we’ve gotta start growing things we can eat…” I fell asleep imagining having a baby and living on food stamps and whatever our acre would grow.

Nick kept the bed right beneath the window. In the morning the sun roused me. It looked like a Saturday of promises. Fat pine tree branches fanned out against a pastel sky. The birds were shrieking. Heat rolled through the screens. The locals would be talking about how hot it was, no doubt, so much ado over such polite heat compared to what I knew. Summer was a cheerful houseguest in these parts, just passing through and careful not to wear out its welcome.

My clothes, all bought before the layoff, bulged from the reduced-expectations closet. I plowed through and put on a bikini and a jersey dress. A declaration. It would do Nick good to spend some time at the town beach.

When Nick woke up he made café au lait. He’d rigged up a picnic table behind the garage so that we could pretend we still had a patio. He set out bagels and we read the print version of the Saturday New York Times, delivered the old fashioned way at the bottom of the steps. One sip of coffee was enough to start him buzzing. He was going to paint the porch himself, a painter had given an estimate of a thousand dollars, and yes that’s right, Melissa was going to be two weeks late with her rent, yeah, last month she was even later, yes there was a pattern but don’t worry, she’d pay it, he was just trying to be helpful and don’t we have to help people we…..He stopped at that thought.

He ran his hand along my cheek and said, “I love your dewy skin.” Six years ago that would have been just the right thing to say. Now what I really wished he’d say was, “don’t worry, we’ll pay the mortgage and get a new car somehow.”

He said, “I think we should let the ants at the bagels and go make love for the rest of the morning.”

But we didn’t go upstairs and make love. He lit upon a photo of a bicycle as he was talking, and announced that we should bike into town and look for paint. He had saddlebags over the back wheel that would carry almost anything. “See, we barely need a car. You can pay for it, can’t you? Don’t sigh like that. We can swim after.”

“We’re going to end up hitchhiking and shooting possums.” I wasn’t supposed to say such things. “My dad would shoot rabbits. They’d never tell you that but you can see it in their faces, people eventually get lines in their faces from scouting in the woods for food let alone frying it up in old bacon grease.”

Nick was looking at me as if I were someone he didn’t know, his eyes like warning lights. Not flashing disdain for the plain girl from the flat place—no, the warning lights said when I pull you down you’re supposed to pull me up. I shivered. He’s going to punish me, something in the back of my head said.

The tears felt alien. I really wasn’t a crier. But I let them cushion his glare. “I feel like…” I was about to come up with some not-guilty plea, but someone was shouting on our property.

More shouts. Human this time. Melissa was having a party.

“Motherfucker git your ass...” Not a party. Something shattered. Wood from the front porch flew in splinters.

“Shit,” muttered Nick.

Two figures emerged, a woman, a man holding her arm, running. Another right behind them, a man with weight-lifter muscles, pouncing before they got to the two feet past the porch where the ground arched. We saw a thrust, and the first man was doubled over. He choked and blood spewed on their grass.

“Go away Charlie.” Melissa was a wispy woman. She came up only to Charlie’s chest. She held herself with arms folded, facing him. She looked liked she might blow away in her filmy blouse and bare feet.

Charlie grabbed her hair. “Fucking cunt.” But he let go when she screamed.

The other guy was up.

“Charlie, get over it. Get outta here.”

“You… and my wife.”

“Uh uh…c’mon get outta here.”

“You got a house? You own a nice house? A place like this but my wife is gonna be selling pussy to pay the rent. We were happy til we lost our house. You know you were happy, you tell him baby…” Charlie was on his haunches now.

“Shit…should we call the police?” That was Nick.

“He doesn’t have a gun.” I made my first stride. My eyes were on the man bent and begging. There were things I knew from a buried place.

“Hey, what’s going on here? I’m the landlady.”

Three faces turned, not hard to tell they were thinking this dusky little girl in playclothes calls herself the landlady?

The lord of the manor was at my side. I had feared for a moment that he might abandon me, but there he was with his philosopher-cyclist biceps, pulling Charlie up by the armpits. “What’s the problem here?”

“No problem.” Charlie shrugged. “We’re having a little talk.”

“Are you all right?” Nick turned to the other man, a guy with flab that looked like baby fat. Blood dripped from the corner of his mouth and spattered his tee-shirt. “What’s your name?”

“This is Bob,” said Melissa. “He’s my friend. As a matter of fact he’s Charlie’s old friend too.”

“I have a right to be here,” muttered Bob through a jaw that wasn’t moving.

“We can take you to the emergency room,” I offered.

“Naw….Gotta get to work… I’ll get some ice at home… I’m fine. Get a life Charlie, I’m still your friend if you need me.”

“Gotta get to work, gotta git..…” Charlie mimicked. “He still gets work.”

“He shows up, unlike some people. Go, Charlie, get outta here. I’ve got witnesses.” Melissa had phantom tears in her voice, tears all dried up and squandered. She had a heart-shaped face and bangs that hung like a remnant from better times. You could see a small town high school beauty in her fading freckles, and in the twist of her upper lip the years with Charlie when things didn’t get better. You could see Melissa as she was going to be someday, delicate but fleshy at the same time and haunting the thrift shops for presents for a brood of grandchildren. You could see that in each of them: Charlie keeping fit but dying young, Bob getting paunchier and someday his back giving out and spending the rest of his life sitting around on disability. And my own husband—I tried to shut it out but I could seem him looking confident on the surface yet growing invisible to the people who mattered.

Bob was walking toward his SUV. Charlie stood, inching toward Melissa as she inched away.

I opened my mouth to make things right. What was that thing you were supposed to do? You distract the predator guy and make him feel like it’s all up to him. Those were things my father used to tell us when he was home for dinner, sometimes on his way out with his holster already strapped on.

“What instrument do you play?”

Charlie’s face said unfair question. “Sax and drums, coupla different bands all around town. I went to college too, y’know. You look like a coupla college graduates.”

Melissa shook her head.

“I came to see my kids.” Okay, that was good. “She sent the kids to her aunt’s. God damn it, why don’t you tell me before I come to see my kids.”

“Yeah, my ex-wife did that too.” Nick was ushering Charlie toward the Chevy. “You come and have a beer with me some night …I’m up here all week on my own and I could use some company… ”

Nick didn’t have an ex-wife. Or a kid.

“You’re a hero,” Melissa said ten minutes later. She was looking at Nick, and her voice was fizzy like a toast to new discoveries. We were in her living room; our living room. She’d pulled the canvas cover off of our sofa, and I saw three stains in the country chintz. The floor had become a sea of teddy bears and dolls, a beach ball, a little red racecar. On the coffee table were two copies of the magazine I used to work for, recent issues that I didn’t leave behind. One shelf of books, six of them novels that had sold over a million copies, eight with titles having to do with finding your inner strength or tapping the power of the zodiac. One new bestseller about why the American dream had turned into a mortgage crisis.

“You wanna make the call?” I asked. Melissa’s hands trembled and her bangs clumped into little stalks, clinging to the sweat on her face like swimmers trying to keep afloat. So I picked up the phone.

When I came back Melissa was all pained effervescence. “The problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world,” she was saying to my husband. She fanned herself. “It’s so hot. Anyway, we watched the whole thing. You know what’s so romantic about, what’s Humphrey Bogart’s name in the movie? Oh yeah, Rick, it’s Rick’s Café. Wish I could get a job there. He comes through when you need him every time, even though he pretends he’s not going to. I thought I was marrying an outlaw hero, you know, when I married Charlie. I might as well tell you, it’s not good to bottle up things. He was always saying what he’d do, like get rich and famous and rescue me. We had schemes.”

“I wrote stuff about the financial instruments that made it possible for you to get a mortgage. It’s my fault you’re in this mess….”

“Yeah, we had get-rich schemes and Charlie never came through, half the time he didn’t even show up. You know what I mean?”

“How long do you think it’s going to take them?” I meant the police, but both Nick and Melissa were immersed in their own therapy roulette.

“You don’t have to stay,” said Melissa. “But it’s good to have company. You shouldn’t be alone and keep things to yourself, all bottled up, I think that’s why my mom got cancer, y’know.”

“We’ll wait with you.” Nick was sitting in his old carved chair from Agadir. He looked almost happy, a trace of the way he’d beamed after he finished a lecture and the room was resounding with chatter.

“Your husband is the best.” Was that a touch of reluctance in the way Melissa turned toward me? “And did he tell you he introduced me to Casablanca? Bob got all misty-eyed. He’s a sweet guy, never gonna be the love of my life. Actually I thought Charlie was. These brooding hunky types, do you ever get old and wise enough to get over them? But you know, it gets lonely here.”

“Tara works her butt off so I can meditate and figure out what I’m going to do with my life.” My husband’s gaze made me feel like a muse, for a moment. When he turned to include Melissa, he smiled as if she could warm a lonely place.

“So what are you going to do with your life?” Melissa asked.

“Oh, I’m starting a teaching job, and I’m going to make a documentary about how people are coping with the economy. I’m writing a proposal to get funding, but if it doesn’t come through, I’ll find it somewhere, or I’ll take out a home equity loan or something.”

“I see you walking around here, guess that’s how you get creative ideas.”

I resolved to ask him, when we were alone, what was this about a funding proposal, and remind him we couldn’t possibly pay off a home equity loan. But I knew he’d pretend he didn’t know what I was talking about.

For now, he was was telling Melissa about how he was going to travel around the country to document how people were living their lives after real estate. “And Tara ought to be in it,” he said, everything about him magnanimous. “Her parents lost their house. Her father was a cop and then a private detective down in Florida. He’s quite a guy, he has a million stories about the things that go on in the estates of Palm Beach. Her mom is a private duty nurse and they always scraped by so their kids could go to college, especially Tara, she was the smart one and they wanted her to go to an Ivy League school and end up in those Palm Beach circles. So what happens, her father got the chance to hit it big and pay for her education anywhere—all because a hotshot lawyer he was investigating for embezzlement offered to pay him off to keep his mouth shut. He did it all for his baby’s benefit, but well, you know, the guy got caught eventually, and Tara’s father testified and got off light all things considered, just lost his license. But then he couldn’t work and they couldn’t pay their property taxes, so they lost the house. He tried to jump off a bridge. Now he sits around all day in a little apartment and he can’t even afford anti-depressants.”

I didn’t bother to point out that my dad only drove to the bridge and sat there a while, didn’t actually try to jump. No one would have listened. And I was enjoying the sight of Nick with his face aglow, like a guy who might actually go home and draw up a grant proposal.

Melissa had her wispy limbs all twined in Nick’s direction. “You’ve got great energy.” She said it to me though her body was pointed at Nick. “Women are stronger than men. Don’t you think? No offense Nick. I just think they are.”

A car drove up and we saw two police walking toward the front door.

“You know if you’re not working you oughtta come to some of these spiritual workshops. I’ll get you the information. I’m taking the advanced one so I can get this certification to lead workshops myself and make some money. It’s expensive but your wonderful husband said I can pay off the rent later.”

Boots thundered on the porch. Melissa went to the door.

Nick was in no hurry to stand up. He looked at me with furrowed eyebrows and a half-smile. “See, this was the right thing to do,” Nick whispered. “Rent the house out I mean.” With so much assurance that for a half-second I imagined Melissa’s check safe in the bank.

Our tenant was shouting “Jimbo!” Then telling one cop that she and the other one had gone to high school together. They were laughing, the three of them. “Ol’Charlie, you let me have a talk with that guy.”

“I think,” Nick whispered to me, “I’m going to reclaim this chair.” He patted the carved arm, and reached out to me with his other hand. As if he were inviting me aboard a magic chariot. I brushed against his knees and it felt electric, for a nano-second. I wish the feeling could have lasted just a little longer.

“Do you think me and the kids are in danger?” I heard Melissa ask her cop buddies, her voice full of hope that they’d say no. Danger. The word hit me like a bullet. I skipped over a trail of toys in the living room that was no longer mine, tore through the dining room and the kitchen and out the back door, pretending I could get away.

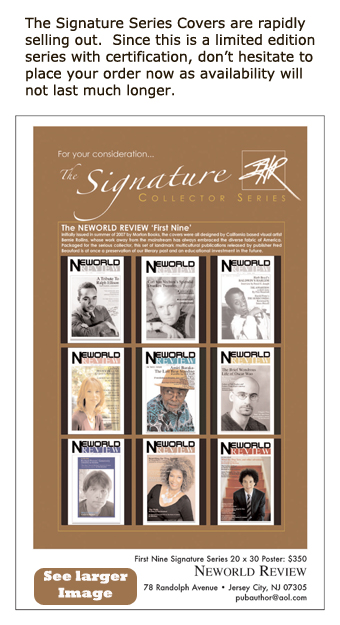

Jan Alexander is editor-at-large for the Neworld Review and author of the novel Getting to Lamma.